Cardiac surgery gives 11-year-old new life

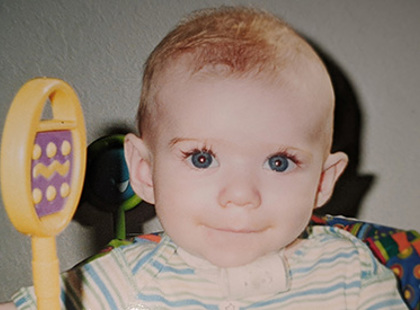

Tyler Bagwell looked perfect when he was born. Ten tiny toes, ten tiny fingers. Eyes the color of the sea. A lusty cry from day one.

But deep inside, something was amiss that set the Virginia Beach boy apart from most of the population: The valve between the left ventricle of his heart and the main artery that distributes blood throughout the body was a little different.

Instead of an aortic valve with three leaflets to regulate blood flow, his had two, something called a bicuspid aortic valve. It’s one of the most common congenital heart defects, affecting an estimated 1 in 50 people.

Tyler was 4 years old when a pediatrician heard the first clue of his unusual valve: A faint clicking sound when the doctor placed a stethoscope against Tyler’s chest. He referred Tyler to CHKD cardiologist Michael Vance, who ordered an ultrasound that revealed the valve defect.

Some people live their whole lives without knowing they even have the defect. In others, the valve becomes leaky enough that they need to have the valve repaired or replaced, usually not until they’re adults. Tyler wasn’t showing any symptoms, so Dr. Vance recommended a watchful waiting approach.

“Our mindset was he wouldn’t need anything until he was an adult,” says Tyler’s mother, Stacie Bagwell.

In early 2018, when Tyler was 10, Dr. Vance discovered he was experiencing “aortic valve regurgitation,” in which blood pumped out of his heart’s main chamber was leaking back in, causing the lower left chamber of his heart to become larger.

Dr. Vance sent Tyler to be evaluated by CHKD’s chief of cardiac surgery Dr. Philip Smith.

Just the thought of heart surgery for her son terrified Stacie. The previous summer, Stacie’s father had died of heart failure, and she had images of his final days in the hospital imprinted in her mind.

But Stacie, a paralegal, and her husband, Ron, who’s a real estate agent, had been noticing that Tyler had lost his energy. He seemed lethargic at times. His skin had become pale.

“I instantly turned to researching everything I could find,” Stacie says.

Stacie walked into that first meeting with Dr. Smith carrying a three-ring notebook labeled, “Tyler’s Heart,” full of studies, procedures, and news of the latest technology.

Dr. Smith sat and talked with the Bagwells about Tyler’s heart valve, the options available to fix it, and the pros and cons of each method. The Bagwells were figuring on, at most, a 30-minute appointment, but an hour later they left Dr. Smith’s office with a thorough understanding of Tyler’s situation.

There was also this: Smith would have a partner in the operating room. He’d be joined by Dr. James Gangemi, surgical director of pediatric congenital heart surgery at UVA Children’s Hospital, and director of the CHKD/UVA regional collaborative for cardiac care.

That’s when the Bagwells learned about the partnership between CHKD and UVA Children’s Hospital. In their minds, that was a distinct advantage.

The official launch of the regional collaborative between CHKD and UVA was in January of 2017, but the effort to bring the two institutions together had been more than a year in the making. The partnership combines the efforts of pediatric cardiologists, cardiac surgeons, cardiac anesthesiologists, intensive care physicians, and cardiac support professionals from both institutions with the goal of sharing knowledge and improving care for children with complex congenital heart defects across the state.

The collaborative allows the hospitals to establish common best practices, create more standardization of care, and make decisions as to the best location for each procedure. Each week, cardiac specialists from UVA and CHKD meet virtually to go over cases from both hospitals, bringing the best minds together to discuss the treatment options.

Smith is based full time at CHKD, and Gangemi performs surgeries at both hospitals.

“We strive to make sure every patient is in the right bed in the right facility at the right time,” says Gangemi.

For Tyler, the right place was CHKD. The Bagwells also sought a second opinion from a children’s hospital outside the state, but continued to meet with Smith and Gangemi, who both passed along their phone numbers and email addresses.

“That was huge to me,” Stacie says. “I didn’t know another doctor who does that and then responds when you do email them. We felt more empowered with each visit.”

In the end, Smith and Gangemi earned the Bagwells' full confidence, and the surgery was scheduled.

Tyler remembers feeling nervous when he arrived early on the morning of September 25. Everyone put him at ease, but they also were clear about the risks he would be facing, right down to the specific mortality rates.

“To have that conversation with an 11-year-old boy would be hard,” Stacie said. “But they did it matter-of-factly, and they didn’t dwell on it.”

Here’s Tyler’s description of surgery: “All I remember is they put a mask on me, and it was like two seconds, and then I woke up.”

His parents got the longer, seven-hour version.

In the waiting room, someone checked in periodically to tell them what was going on. “That was like a glass of water to a person in a desert,” Stacie says.

As sophisticated as imaging scans have become, there are still things that can only be determined once surgeons open the chest and train their eyes on the heart.

In Tyler's case, they wanted to see if the valve could be repaired.

It couldn’t.

The next option was using the Ross procedure, in which the patient’s pulmonary valve is swapped out with the damaged aortic valve. The advantage of using a pulmonary valve is it can continue to grow normally in a child who isn’t fully grown, better handling the high volume of blood.

Once the surgeons got a first-hand look at Tyler’s pulmonary valve, though, they ruled out that procedure because that valve looked a little different, too.

It was working fine as a pulmonary valve, but the aortic valve is under greater blood pressure, so the doctors didn’t want to take the risk of using a valve that might not be up to the job.

Gangemi “scrubbed out” of the surgery to let the Bagwells know they were forgoing the Ross procedure, and going with a mechanical valve. The surgical decisions were played out in real time, but each option had been thoroughly explained to the Bagwells in advance, so there were no surprises.

Once the doctors replaced the faulty valve with a mechanical one, Tyler’s heart began pumping better, something the surgeons could see even before Tyler left the operating room.

Because of her memories of her father’s last days in the hospital, Stacie walked into Tyler’s recovery room with some trepidation: “When we saw Tyler, I felt an immense sense of relief. He was pretty groggy, but my same beautiful boy. He was OK. I was OK. My husband and I didn’t collapse on the floor. The staff treated us as much as they treated Tyler.”

The Bagwells took Tyler home a week later, with this advice from Dr. Smith: “Be cautious, but don’t change your expectations of him.”

The hardest part of recovery, according to Tyler: “Not carrying the cats.”

He’s well past that now, but his life is different. For instance, he’s on blood thinners because of the artificial valve. He wears a medic alert necklace noting the valve. And there is the periodic monitoring, along with the question of whether the valve will ever need replacing.

The Bagwells were impressed with how carefully the doctors explained everything to them and Tyler, and how CHKD staff members treated not just the patient but the whole family during the hospital stay. So much so they want to reach out to educate others.

“I think it’s important for parents to talk with others who have been there,” Stacie says. “Despite our fears and concerns, Dr. Smith and Dr. Gangemi steadfastly stood by, allowing us to ask questions, share fears, and consult my notebook.”

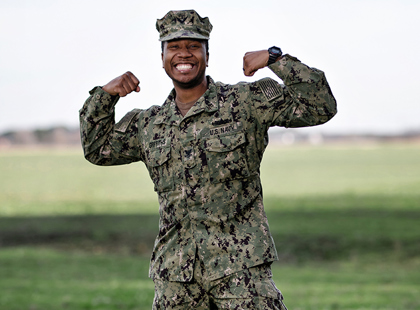

Tyler’s color has improved. He runs around more. He can exercise longer. The handsome young man with a ready smile describes the difference in one simple sentence: “I have more energy.”

Published in CHKD's KidStuff Magazine, Winter 2019

Written by Elizabeth Earley • Photograph by Susan Lowe